It was the ancient Greeks who first coined the idea, and word, ‘icon’ – or eikenai – meaning ‘to seem’ or ‘to be like’, and in so doing captured the symbolism of the religious practices through which supplicants were drawn onto some higher ideal.

Their gods – who were in essence their values abstracted – could be realised only in the form of the statues and figurines that were to represent them. Some things are too lofty, the Greeks knew, to abide this fallen plain, requiring a middleman of sorts, a conduit able to be both celestial yet natural, beyond sight and yet seen – like dreams, speaking to us of those things too transcendent for our common tongues and minds to hold.

In many ways, my favourite writers have been like this, standing, in my mind, for an ideal, a way to see and think that lies somehow within and beyond their words. These writers did not advise ‘write what you know’, that most unconscionable of counsel for the creative mind, but instead nudged me, taking my elbow in hand to steer me toward some new horizon I’d been too shallow or juvenile to realise was there. ‘Look’ they say, ‘Here is a way. Here lie many paths,’ and, by their genius, enlighten and broaden the soul, teaching it to understand in itself the voice with which it must speak, the world from which we must write.

My first experience of this was in encountering the astounding work of David Foster Wallace, whose formidable intellect and wit fills both his fiction and essays the way his often long, grammar-defying sentences fill the page. And yet in spite of this, perhaps somehow even because of it, there remains a warmth and feeling to his writing. In essays like ‘E Unibus Pluram’ and ‘Consider the Lobster’, and even in the fastidious examination of addiction and entertainment culture that is his masterpiece, Infinite Jest, Wallace seems to be agitating for a world that is more at peace, where the soul has been more aptly reconciled unto itself in some way.

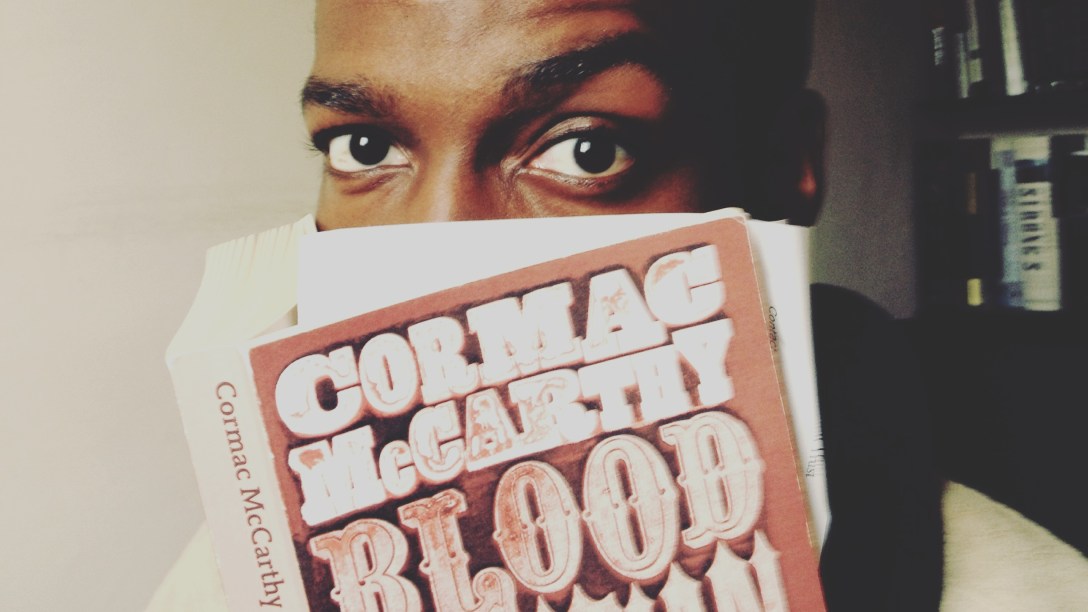

But where Wallace seeks to look inward, circumscribing a certain hollowness, a sense of something missing in the modern-day human condition, Cormac McCarthy, another of my literary eikenai, is more interested in turning the attention outwards to the beyond – ‘Out there past men’s knowing, where stars are drowning and whales ferry their vast souls through the black and seamless sea.’ There is something of an almost religious fervour to McCarthy’s searing prose, as though the world, to him,

had been dipped in the ink of gods before being taken wholesale and scrawled onto the page.

In a very different way, Octavia Butler – the last of my icons – completes the project. Through her I discovered the true scope and possibilities of her genre, science fiction. Her imagination is as vast as McCarthy’s, but where his is poured into his prose, hers conjures worlds. But what separates Butler from her peers is not the impressive depth of the fantastical realms in which her tales are set, but the way she does not allow their scale and detail to subsume the intimacy of them. The eviscerating power and brevity of Bloodchild is a perfect example, managing to evoke the violation and oppression of slavery through the lens of an imagined alien occupation and the forced symbiosis that ensues.

Each of these three are more than authors. They are prophets – those who’ve learned to see the world anew, to hold within themselves the burden of truths conceived beyond the limits of their own experiences. By their words, and more than that, their perspective, they not only entertain: they edify – they agitate; convey an argument; provoke thought. Teach. And so perhaps that’s what makes reading them so compelling, in that they have harnessed what story and literature were always meant to be – in reading them we find something more than mere enjoyment. We find growth. We are added to, and drawn beyond ourselves into the hopes and questions of what life is and can become.

A recording of this talk can be found at writersmosaic.org.uk

Subscribe

Get notified of the latest posts by email.